Peter Greenhill, SHA

Despite delays by unreported bomb scares in a media-weary metropolis, ten members of the SHA assembled at the Sovereign’s Entrance of the Palace of Westminster for a private sponsor’s visit to the House of Lords, kindly organised by Robert Harrison, by permission of the Archivist and the seal of Black Rod’s office. Extreme good fortune allowed us the privilege of a private tour conducted by one of our most knowledgeable associate members, Keith Lovell, FHS. Keith’s boundless enthusiasm for his subject made two and three-quarter hours seem like a passing moment.

Despite delays by unreported bomb scares in a media-weary metropolis, ten members of the SHA assembled at the Sovereign’s Entrance of the Palace of Westminster for a private sponsor’s visit to the House of Lords, kindly organised by Robert Harrison, by permission of the Archivist and the seal of Black Rod’s office. Extreme good fortune allowed us the privilege of a private tour conducted by one of our most knowledgeable associate members, Keith Lovell, FHS. Keith’s boundless enthusiasm for his subject made two and three-quarter hours seem like a passing moment.

The Palace of Westminster was the residence of the Sovereign from Edward the Confessor to King Henry VIII and occupied eight acres of land beside the River Thames. On 16th October 1834, several cartloads of tally-stick accounts were trundled from the Tally Room to the House of Lords furnace for burning. The furnace overheated and burnt down the building. Within 24 hours only Westminster Hall, the cloisters, crypt and jewel tower were still intact. Though this was a terrible disaster it did present the opportunity to create a more sumptuous purpose-built edifice that was to become one of the finest examples of Victorian Gothic in the land. This was thanks primarily to two men: the architect Sir Charles Barry and his extraordinarily gifted assistant, the 22-year-old Augustus Pugin.

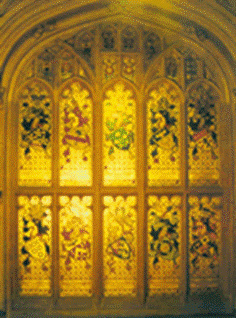

We entered by the Victoria Tower and were frisked for terrorist appendages as we reached the landing below the Royal Staircase, ascending to the Robing Room. Splendid in red and gold, it introduced portraits of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, part of a continuing theme of huge family pictures. Most are said to be copies of originals secreted in other royal homes, by Winterhalter, Hayter, Kelly and the like. Heraldry abounds on every side, overhead and underfoot; a Victorian reminder of illustrious ancestors and a serious attempt to replicate mediaeval influences. A giant statue of Henry V did not look out of place despite displaying France ancient on his quartered jupon. In the same Royal Gallery, a frieze of escutcheons charted the progress of England’s monarchy. This massive room was dominated by two facing frescos of Nelson and Wellington by Daniel Maclise (reminding us of Vasari in Florence) and leads to the Prince’s Chamber.

We entered by the Victoria Tower and were frisked for terrorist appendages as we reached the landing below the Royal Staircase, ascending to the Robing Room. Splendid in red and gold, it introduced portraits of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, part of a continuing theme of huge family pictures. Most are said to be copies of originals secreted in other royal homes, by Winterhalter, Hayter, Kelly and the like. Heraldry abounds on every side, overhead and underfoot; a Victorian reminder of illustrious ancestors and a serious attempt to replicate mediaeval influences. A giant statue of Henry V did not look out of place despite displaying France ancient on his quartered jupon. In the same Royal Gallery, a frieze of escutcheons charted the progress of England’s monarchy. This massive room was dominated by two facing frescos of Nelson and Wellington by Daniel Maclise (reminding us of Vasari in Florence) and leads to the Prince’s Chamber.

This anteroom encapsulated all that Pugin wanted to say about the Victorian place in history. Overseen by a vast marble statue of Queen Victoria enthroned by John Gibson, this dainty room displays a charming educational frieze of full-length royal portraits on gilded leather.

The House of Lords Chamber of red and gold, though sumptuous, has a strange theatricality about it which challenges the seriousness of its purpose, almost as if needing to impress the eye with its importance. The colossal golden dais displaying the throne overlooks the wool sacks and the deep-buttoned benches. Crossing the immense Central Lobby at the epicenter of the Palace, the furnishings change from red to green to emphasize the Commons. Through to the Commons Lobby and not forgetting to touch Churchill’s foot for luck, we enter the House of Commons. The severity of Sir Giles Scott’s Chamber, rebuilt after enemy aircraft destruction in 1941, is something of a shock but more restful on the eye. Standing on the floor ‘two sword lengths’ between the boundaries that members may not overstep, the room feels quite small and manageable and the voice carries without interruption.

The House of Lords Chamber of red and gold, though sumptuous, has a strange theatricality about it which challenges the seriousness of its purpose, almost as if needing to impress the eye with its importance. The colossal golden dais displaying the throne overlooks the wool sacks and the deep-buttoned benches. Crossing the immense Central Lobby at the epicenter of the Palace, the furnishings change from red to green to emphasize the Commons. Through to the Commons Lobby and not forgetting to touch Churchill’s foot for luck, we enter the House of Commons. The severity of Sir Giles Scott’s Chamber, rebuilt after enemy aircraft destruction in 1941, is something of a shock but more restful on the eye. Standing on the floor ‘two sword lengths’ between the boundaries that members may not overstep, the room feels quite small and manageable and the voice carries without interruption.

The Canadian table supports the two elegant honey-coloured brass-bound despatch boxes, reminding us of many a leaning discourse, overseen by the Speaker’s Chair. We return via the Central Lobby to St Stephen’s Hall. Previously at the royal chapel, the Commons met here for more than 280 years before the “tally” fire. The murals and statuary are another celebration of the Victorian viewpoint; interesting floor tiles remind us of a chivalric past. En route we have detoured to view Baz Manning’s contribution to the building’s history, specifically the Arms of the Chiefs of Defence Staff on the Peers’ Staircase, with Lords Chancellor and Speakers’ Arms yet to follow.

Finally, we arrive at William II’s Westminster Hall, an enormous stone room that spans 900 years of British history. Originally post-lined these supports were removed at the end of the 14th century, when Richard II had them replaced by a magnificent hammer beam roof. Flying carved angels hold royal shields on high over the heads of stone monarchs. London’s bustle echoing from New Palace Yard nearby reminds us that this hall used to be lined with shops, but Thomas More, Guy Fawkes and King Charles I were sentenced here.

Our thanks to Baz and Robert for organising this event, and three cheers to Keith for so generously sharing with us his endless knowledge of one of his favourite buildings. §